We constantly encounter new microbes, but very few of these microbes become long-term residents of the human gut microbiome. When and why do new microbes successfully colonize established gut communities?

As a postdoctoral fellow in the labs of David Relman and Dmitri Petrov at Stanford University, I investigate the ecological factors and microbial interactions that affect colonization by combining longitudinal, controlled human studies with high-throughput in vitro community experiments. My work has been supported by postdoctoral fellowship from the James S. McDonnell Foundation and the Jane Coffin Childs Memorial Fund for Medical Research.

Tracking colonization dynamics

in the human gut microbiome

When do new microbes colonize the human gut microbiome?

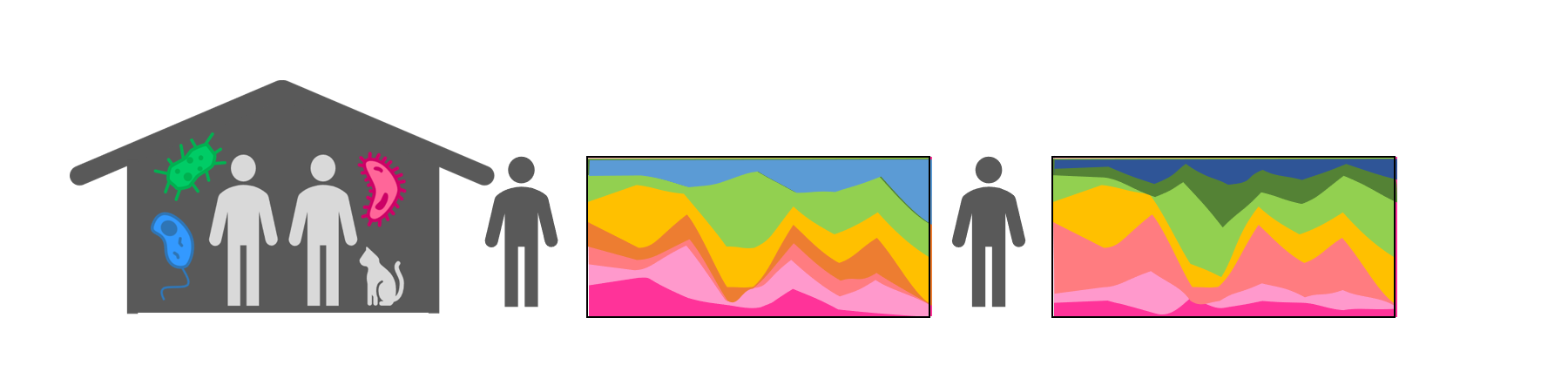

I perform quantitative, longitudinal community surveys to track colonization dynamics “in the wild,” in the human gut microbiome. During my postdoc, I designed and carried out a longitudinal household study to track the dynamics of colonization before and after a controlled antibiotic perturbation (Xue et al., bioRxiv 2023). I initially expected antibiotics to create an ecological vacuum and that new strains would rush in to fill the gap. Surprisingly, however, I saw that even after antibiotics cause extensive species losses in the gut microbiome, new strains still take months or years to colonize. These results show that there remain strong ecological barriers to colonization even after major microbiome disruptions, suggesting that dispersal interactions and priority effects limit the pace of community change.

Xue, K.S.*, Walton, S.J., Goldman, D.A., Morrison, M.L., Verster, A.J., Parrott, A.B., Yu, F.B., Neff, N.F., Rosenberg, N.A., Ross, B.D., Petrov, D.A., Huang, K.C., Good, B.H.*, Relman, D.A.* Prolonged delays in human microbiota transmission after a controlled antibiotic perturbation. bioRxiv (2023). DOI: 10.1101/2023.09.26.559480. *corresponding authors

Characterizing the microbial interactions

that shape colonization

What microbial interactions determine colonization outcomes?

To characterize the microbial interactions that affect colonization success, I bring gut microbial communities into the lab, where we can perform controlled, high-throughput colonization experiments. I have built a collection of in vitro gut microbial communities derived from pre- and post-antibiotic samples in my household cohort, and I have used these in vitro communities to investigate how the number of introduced microbes affects their colonization success (Goldman*, Xue*,†, et al., bioRxiv 2023). We found that initial population size could have surprisingly long-lasting effects on colonization outcomes, especially in diverse communities, where introduced species have high niche overlap with resident species. Moving forward, I plan to use these in vitro communities to investigate how resource competition, spatial structure, and bacterial antagonism shape colonization outcomes.

Goldman, D.A.*, Xue, K.S.*,†, Parrott, A.B., Jeeda, R.R., Lopez, J.G., Vila, J.C.C., Petrov, D.A., Good, B.H., Relman, D.A., Huang, K.C†. Competition for shared resources increases dependence on initial population size during coalescence of gut microbial communities. bioRxiv (2023). DOI: 10.1101/2023.11.29.569120 *equal contribution, †corresponding authors